The mental load of running a household is the invisible labor behind every home: the constant thinking, planning, and organizing. It’s not washing the dishes. Iit’s remembering that they need to be washed, checking whether there’s any detergent left, calculating when you’ll have time to do it.

Even when the house is clean, the mind doesn’t stop. The sheets need to be washed on Wednesday. The air conditioner filter needs cleaning. We’re running out of paper towels. In two days the bathroom will be dirty again. The kids will need clean clothes for school on Friday.

This constant mental work has a name in international research: cognitive household labor. And data shows it is far more exhausting than the physical chores themselves.

The phenomenon that went viral

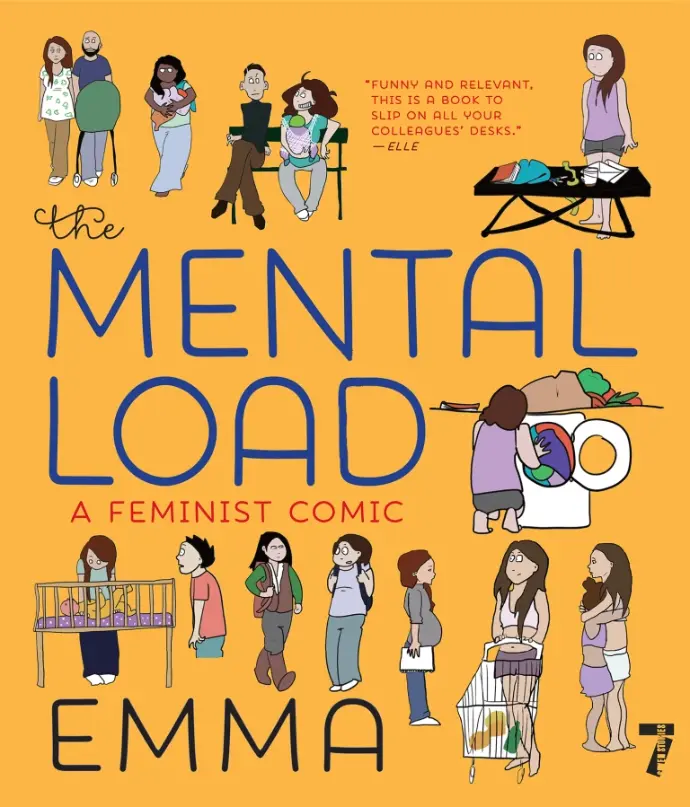

This feeling of continuous mental labor isn’t new - but only in recent years has it found its voice. In 2017, French illustrator Emma published a comic titled “You Should’ve Asked”, which went viral worldwide. It described something millions of people - mostly women - experience daily: exhaustion not from doing the chores, but from remembering, organizing, and tracking everything.

Emma’s viral comic sparked the conversation. But how big is this problem really? Scientific research offers clear answers.

How unequal is the distribution?

A study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family (2024), involving 3,000 parents in the U.S., found that mothers estimate they take on 71% of the household’s mental labor, while fathers estimate their own contribution at 45% - a gap that reveals how invisible this labor remains, even to partners themselves. For daily, recurring tasks, the difference is even greater: mothers report handling 79% compared to fathers’ 37%.

Research by the Pew Research Center (2023) confirms the pattern: 78% of mothers in couples say they do more in managing children’s schedules and activities 65% say they provide more homework help 58% say they take on more emotional support. But beyond percentages and statistics, what does this imbalance look like in everyday life?

But beyond percentages and statistics, what does this imbalance look like in everyday life?

What this means in practice

Women often become the de facto household managers.

A man may wash the dishes - but the woman remembers that the detergent is running out.

A man may vacuum - but the woman knows when the vacuum bag needs replacing.

A man may cook - but the woman plans what the family will eat next week.

The problem is that this mental labor has no schedule. It doesn’t “end” when the day ends. It continues on the couch, in bed, on vacation. And this continuous, never-ending work has consequences, not only for household functioning, but for health itself.

The impact on health

A study published in the Archives of Women’s Mental Health (2024) by the University of Southern California, involving 322 mothers with young children, found that women with high mental load reported:

- Higher levels of depression

- Increased stress

- Lower relationship satisfaction

- Symptoms of burnout

The study found that mental load had a greater impact on psychological health than the unequal distribution of physical tasks. Yet this exhaustion often remains hidden, trapped behind a simple word we all use: “nothing.”

The “nothing” that isn’t nothing

Behind the irritated “nothing” often lies exhaustion from mental load. It’s not anger about one specific chore that wasn’t done. It’s the accumulation of weeks, months, years of being the one who remembers everything for everyone, without anyone noticing.

Psychologists specializing in family relationships describe a common pattern:

Exhaustion: “I’m tired all the time.”

Invisible labor: “No one sees how much I do.”

Loneliness: “I carry this burden alone.”

Anger: “Why do I have to tell everyone what to do?”

Guilt: “Am I complaining about nothing?”

And behind all these feelings lies something even more exhausting: the sense that there is no end.

The endless list

I need to clean the bathroom. I need to change the sheets. I need to go grocery shopping. I need to check if there’s toilet paper. I need to dust.The list never ends. Every time you cross off one item, three new ones appear. There is no “finish.” There is no moment when you can say, “I’m done forever.” Even when the house is clean, the brain doesn’t relax, because it knows tomorrow everything will need to be done again.

At this point, many suggest a simple solution. But is it really that simple?

Why “just don’t think about it” doesn’t work

Many recommend a “relaxed approach”: “Don’t stress so much. It doesn’t matter if everything isn’t perfect.” The problem? Mental load is not a choice. It’s the result of years of social expectations and real needs. You can’t “just stop thinking” that your children need clean clothes for school. Or that there’s no food in the fridge.

The solution isn’t to “relax more”. It’s to reduce the actual load. But to reduce it, we must first understand a key difference that often gets overlooked in discussions about dividing chores.

Help or support?

There is a crucial difference:

- Help: I do a task when I’m asked.

- Support: I take full mental responsibility for a task from start to finish.

Example:

- Help: “Tell me what to buy and I’ll go.”

- Support: “I’ll check what’s missing, make a list, shop, and put everything away.”

In the first case, you remember, plan, and organize, the other person simply executes. In the second case, the other person takes ownership of the entire process.

Support means autonomy. Taking on part of the mental labor, not just the physical task. Understanding this difference helps clarify what truly needs to change.

What can you change?

Acknowledging the problem: The first step is recognizing that mental load is real work. It’s not imagination. It’s not perfectionism. It’s the weight of constant organization, planning, and responsibility.

Clear division of responsibilities Instead of “I’ll help wherever needed,” research shows that clearly dividing areas of responsibility reduces mental load.

Example:

- You: Responsible for the kitchen (groceries, cooking, cleaning)

- Partner: Responsible for bathroom and laundry (cleaning, washing, ironing)

When responsibility is clear, no one waits to be told what to do.

Professional support: Beyond dividing responsibilities at home, there’s an important truth many struggle to accept: you don’t have to do everything yourself. Professional household support isn’t a luxury - it’s a practical solution that reduces mental load.

And this is exactly where Worryla comes in, with a different approach to household support.

Worryla: When cleaning is more than just a task

Worryla understands that household support is not just about cleaning. It’s about comprehensive home care and reducing continuous mental labor.

When a Worryla caregiver comes to your home:

- You don’t have to remember when cleaning needs to be done, there’s a clear schedule

- You don’t have to explain what needs to be done, there’s a clear work plan

- You don’t have to worry if it will be done properly, there’s a quality guarantee

The result? A whole part of your mental load simply disappears. Instead of constantly thinking: “I need to clean.” “When will I find time?” “Did I do it properly?” You simply know it’s taken care of. Your home becomes a place where you live - not a place you constantly manage.

he solution is not to “try less,” but to truly share the load. Professional help. Clear division of responsibilities. Recognition of invisible labor. These are steps toward a healthier relationship with your home, and with yourself.

Because your home should not be a constant source of stress. It should be a place where you can truly relax.

If you’d like to learn how Worryla can support you:

Call us at: +30 210 700 2000, Monday to Friday, 09:30–18:00

Or simply fill in our Communication Form: https://www.worryla.gr/contactus

Sources

Weeks, A. C., & Ruppanner, L. (2024). A typology of US parents' mental loads: Core and episodic cognitive labor. Journal of Marriage and Family, 87(3), 966-989.

Aviv, E., Waizman, Y., Kim, E., Liu, J., Rodsky, E., & Saxbe, D. (2024). Cognitive household labor: Gender disparities and consequences for maternal mental health and wellbeing. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 27(4), 665-676.

Pew Research Center. (2023). Gender and parenting: How mothers and fathers differ in their approach to raising children. Survey conducted Sept. 20-Oct. 2, 2022.

Daminger, A. (2019). The cognitive dimension of household labor. American Sociological Review, 84(4), 609-633.

Emma. (2017). You Should've Asked [Fallait demander]. The Mental Load: A Feminist Comic.